|

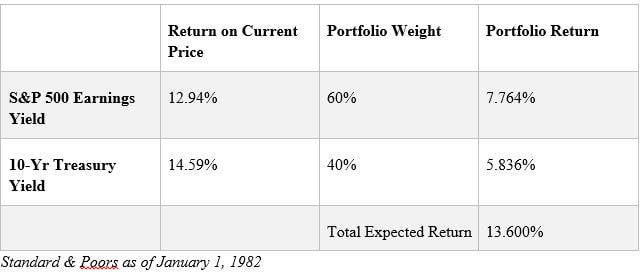

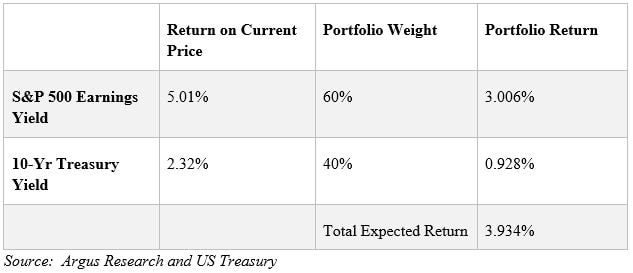

In one of our meetings, Justin asked a question of me. He said, “Why is it that the only investment managers telling people to be careful are old timers like you? Jeremy Grantham of GMO, whose seven year forecast is negative in all asset classes other than emerging markets. Howard Marks, whose most recent memo “There They Go Again…Again” strongly suggests people be cautious in their investing today. John Hussman, who has been screaming at the top of his lungs about the “overvalued, overbought, overbullish” markets. Seth Klarman who, at least from what we hear, is sending money back to his investors due to an absence of good opportunities. And finally Warren Buffett, the most recognized value manager in the world, whose Berkshire Hathaway is holding billions, not because he wants to sit on the cash, but because like Klarman, he is struggling to find options available at a reasonable price to purchase. I thought about it for a while and said, “Well, it could be that of those you mentioned, we all tend to be contrarian value investors who believe that successful long-term investing requires buying at a low price. Or it could simply be that we are all just a bunch of grumpy old men!” All of us have had run-ins with a grumpy old man. He may be the guy you never want to run into at lunch, because to him the whole world is screwed up. He tells you the economy is terrible, the government is bankrupt, no one can find a job, everyone is in debt, and the future for our kids and grandkids is dismal. I will admit that I try hard not to assume my role as a grump, though at times I do find myself slipping. When I do, both Justin and Libby are quick to remind me of my deficiency. Yes, all of us old time investment managers making a case for conservative investing may just be grumpy, but today, I am going to assume that we are not. I will assume that we have learned from decades of experience managing portfolios for others. All of these “old men” have lived through an exceptional period of time for long-term conservative investors. According to Goldman Sachs, a traditional 60/40 portfolio, (60% invested in the S&P 500 index stocks and 40% invested in 10-year US Treasuries) generated a 7.1% inflation-adjusted return since 1985, compared with 4.8% over the last century. Maybe these exceptional returns have turned us into grumps wishing for the old days when it was easier to manage portfolios. Easier because there was always a choice to balance a portfolio based on price. When common stocks were expensive relative to risk free treasury yields, you just sold a little stock and increased the bond holdings at a rate exceeding the rate of inflation. Then you would wait until common stocks became cheap again. Of course they always did, sometimes with a bang, other times with a whimper, but you knew you could just wait it out. Today that option is limited, as current interest rates do not cover inflation, let alone taxes and fees. Those of us who make our living as analysts or portfolio managers understand the quantitative use of the risk free interest rate in the valuation of common stocks. The few of us managers who have been around since the early eighties have a first-hand knowledge of the extreme influence short term rates have on investor opinion. I bring up the early eighties because it was the last time both common stocks and bonds were extremely cheap, yet individual investors failed to take advantage of this extreme. Shortly before Paul Volcker, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve at the time, was determined to break the back of inflation, the mutual fund industry created the money market fund. This provided a low risk interest bearing investment with check writing privileges that paid interest earned in the “money market.” These funds paid, as they do today, a floating rate that increased or decreased relative to short term rates that were for the most part controlled by the Federal Reserve. When Mr. Volcker increased rates to the extreme, money market funds were paying in excess of 20%. During this time, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was below 800, with an earnings yield above 14%. The thirty year Treasury bond reached 15%, and 10 year FDIC insured CDs were yielding 17%. You’d think it would have been easy for everyone to take advantage of this great opportunity, but that wasn’t the case. Most individuals just wanted to open a money market mutual fund. Today, we are now at another extreme, only this time it seems everything is expensive. The Dow Jones Industrial Average is above 24,000, the S&P 500’s earnings yield, based on 2017 consensus earnings of $132.75, is 5.01%, and the 10 year US Treasury Bond is yielding 2.32%. This is why us grumpy old men are cautious. Not because we feel the economy is terrible, debt is unmanageable, or the future is doomed, but because on average, everything is more expensive than it has been for decades. I want to clarify this difference in expected returns from the early eighties to today based on the S&P 500 index and the 10 Year Treasury Bond. Expected Returns from a 60/40 portfolio in 1982: Expected Returns from a 60/40 portfolio today: Being cautious does not mean running for the hills, selling your stocks and bonds, and putting your money in a can buried in the back yard. It does mean you must be prepared for the possibility of lower future rates of return. For so many of us, we have become used to double digit returns on our investments. We may have even increased spending or reduced the amount we are saving based on the returns earned in the recent past. We should be prepared for an adjustment in prices on both common stocks and bonds. For example, if you purchase the 10 year treasury and hold it to maturity, all you will earn is 2.32%, the yield today. For common stocks, you should expect an adjustment in price. Even if earnings continue to increase, even if the economy continues to improve, even if dividends continue to increase, prices will adjust, and we just hope they do not adjust with a big bang. If earnings in the next twelve months reach $145.25, the current consensus estimate for the S&P 500, the index could easily decline to its historical multiple of 15 x earnings, or 2178, close to an 18% decline.

Will the markets decline, and will interest rates stay the same or increase? I wish I could give you the answer, but I cannot. Knowing that market prices are higher than historical averages, and interest rates are lower than historical averages, does help guide us in the construction and maintenance of portfolios. It helps us recognize that easy money from owning common stocks and bonds is probably over. That great opportunities are few and far between, and that a cautious approach for a conservative investor is warranted. Of course we could be wrong, and caution could result in a less than average rate of return. We must be willing to accept that. We also know that opportunities will make themselves available independent of averages. We don’t know when, or for that matter what, these will be, but we will be prepared to take advantage of them when they arise with the reserves we have been building in portfolios. Until next time, Kendall J. Anderson, CFA Comments are closed.

|

Kendall J. Anderson, CFA, Founder

Justin T. Anderson, President

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Common Sense Investment Management for Intelligent Investors

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed