|

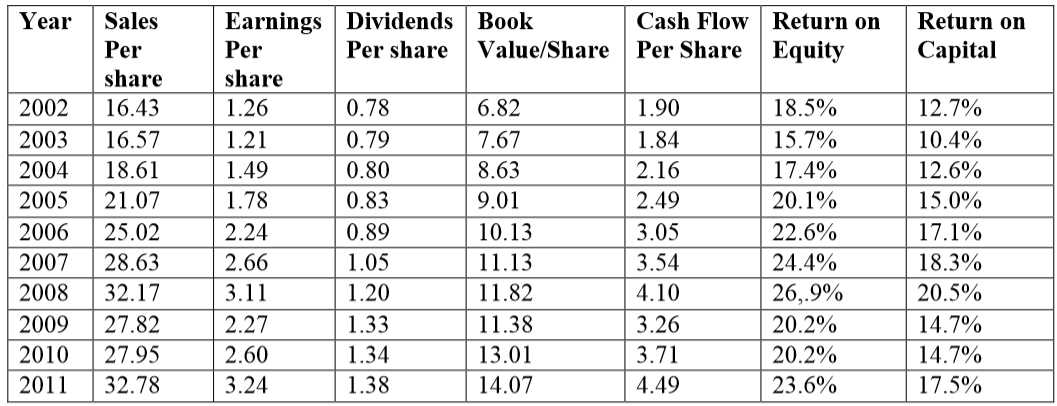

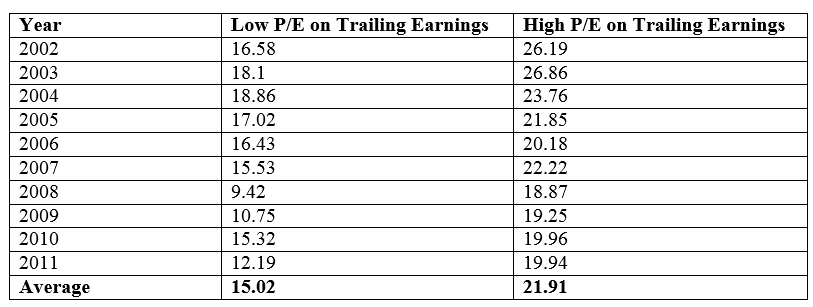

Ben Graham may not have been the first to use the term “intrinsic value” as a form of analysis for stocks and bonds. But, through his teachings and the successful application of this approach by his many students and practitioners (including Warren Buffett, John Templeton, Seth Klarman, Mason Hawkins, Howard Marks and yours truly — not to imply that I am in the same category as those mentioned, but a believer none the less) he is given the credit. Understanding the concept of intrinsic value is necessary for an intelligent investor. Without understanding intrinsic value, its offspring, “margin of safety”, has no meaning. Intrinsic value may not be a term you have heard, however, you may have heard of similar ones: indicated value, target price, normal value, reasonable value, central value, fundamental value, and our favorite, fair value. Before we delve into a better understanding of intrinsic value, I thought I would give you a little history from the PC days. PC, in this instance, does not mean politically correct or personal computer. To me, it is an easy way to date my first venture into the field of investment analysis — a time of books and calculators, the time before personal computers, the pre-computer age. As a brand-spanking new investment salesman, the approach to success in the business was simple. You just did what your firm told you to do. Make the calls, ask for the orders, and forget about analysis as your firm was your guiding light to what was a good investment. Without investment training, this approach seemed logical. After all, who was I to tell the big investment houses how to choose stocks and bonds? A young man with a business degree and no money in the bank surely couldn’t do a better job than them. So that is what I did until the losses came. This approach, doing what your firm recommends, is in most cases appropriate for all financial advisors. It will at least give you a fighting chance to stay in the business and make a respectable living for yourself and your family. For me, it was not enough. No matter how hard I tried to place the blame of investment mistakes on my firm, my clients would not accept that excuse. And since they held me responsible, I owed it to myself to learn a little more about investment analysis. So the search for knowledge began. Anticipation The first foray began with trying to answer the question that all of us would like to know, will the market go up or down? This top down anticipation approach has nothing to do with attempting to value an individual common stock or bond, yet, it is the most widely accepted approach by economists, investment firm strategists, tactical asset allocators and the average investor in the PC, as well as, current days. It is accepted for a couple very simple reasons. The first is that we believe the idea that as the economy goes, so goes the stock market. The second is because we could easily get rich by buying the market before it goes up and selling the market before it goes down. It did not take me long to realize this approach would have a hard time helping my clients create wealth. As I studied the record of economist forecasts the results were fifty-fifty. Half of them got it right, the other half wrong. The bigger problem is those that got it right the first time almost never got it right the second time. And even when they were right, the market did not follow the predictions. In fact it seemed almost the opposite leading me to the conclusion that the best time to buy was when the predictions called for a bad economic future and the best time to sell was when the future looked great. The results on market timing were even more dismal. From what I could find, market timing was the easiest way to lose wealth. Through my own experience, I knew that most investors would buy high and sell low. If they sold low, they would stay out the market until it recovered, then buy their shares back only to lose a little more the next time the market declined guaranteeing themselves as a member in good standings of the world famous buy high sell low club. Attempting to time the market did have one enduring quality for a new salesman: it created a lot of commission income at a time when commissions were never discounted! Relative Valuation Once I wrote off these concepts I explored the idea of relative valuation, looking at an individual common stock or bond relative to the market for each. In choosing bonds, spread, the difference in yield between one bond and the market rate of bonds in general, was the preferred approach. Maybe it was the time, but I was able to do a great deal of damage using a process dependent on relative valuations. Bond yields changed dramatically over time and a positive spread for one day or month did very little to protect the market value of bonds when interest rates changed. The same held true with common stocks. For common stocks, the measurement was the price earnings multiple of one company versus the average price earnings multiple of the market. It was not fun to watch your stock price decline when a P/E was a relative bargain at the date of purchase but the market P/E changed from 20x earnings to 14x earnings. Intrinsic Value Knowing what doesn’t work for me was a step in right direction, but it didn’t solve anything. I still did not have a theory to live by until I was introduced to Benjamin Graham and his concept of intrinsic value. As it was with many investment professionals, this introduction was made through his book Intelligent Investor and then followed by Graham and Dodd’s Security Analysis. In chapter 2 of the second edition of Security Analysis, Graham and Dodd offered “The Relationship of Intrinsic Value to Market Price” found on page 28: The general question of the relation of intrinsic value to the market quotation may be made clearer by the following chart (found on page 29), which traces the various steps culminating in the market price. It will be evident from the chart that the influence of what we call analytical factors over the market price is both partial and indirect—partial, because it frequently competes with purely speculative factors which influence the price in the opposite direction; and indirect, because it acts through the intermediary of people’s sentiments and decisions. In other words, the market is not a weighing machine, on which the value of each issue is recorded by an exact and impersonal mechanism, in accordance with its specific qualities. Rather should we say that the market is a voting machine, whereon countless individuals register choices which are the product partly of reason and partly of emotion. In the fifth edition of Security Analysis, Sidney Cottle, Roger F. Murray and Frank E. Block updated Graham and Dodd to reflect the changes that had occurred in the market place since the fourth edition was published some twenty five years earlier. They dedicated an entire chapter to intrinsic value. I like their introduction. This paragraph is found on page 41: Intrinsic value is the investment concept on which our views of security analysis are founded. Without some defined standards of value for judging whether securities are over- or underpriced in the market place, the analyst is a potential victim of the tides of pessimism and euphoria which sweep the security markets. Equally destructive of satisfactory investment are the fads and herd instincts of major participants in the marketplace. For security analysis to contribute positively to the investment decision-making process, the discipline must provide a basis for resisting the pressure to be either a passive follower of prevailing sentiment or a mindless contrarian committed simply to thinking in opposite terms from the consensus. Being young and full of myself, I did not understand the meaning of intrinsic value for a number of years. Instead I attempted to use the weighing machine approach, without paying much attention to the markets voting power. The weighing machine is the down and dirty work of security analysis. It is a number crunching game. And I jumped in with both feet. In PC days, I relied on the monthly stock guide, a little paperback book published by Standard and Poors that provided some basic fundamental data on approximately 5,000 publicly traded securities. I supplemented this with the printed version of the Value Line Survey that provided historical fundamental data on 1,700 companies. With Moody’s as a backup I felt as if I could somehow find a “system” based on a combination of fundamental data that would make myself and my clients rich beyond our wildest dreams. Riches never followed. However, all was not lost. Monthly, I diligently went through the stock guide, armed with a calculator; adding and subtracting, multiplying and dividing numbers to find a relationship between income statement items and the balance sheet. To understand the prices relative to earnings and dividends as compared to each other company in the guide. These hours spent may not have had a short-term payoff; however, I learned a couple things that have paid off tremendously. The first is that no system will work without considering the “voting machine” of the market. The second is that I developed a deep understanding of the relationship between assets and earnings power. (I also became a pro on the calculator!) The traditional definition of intrinsic value relies on the assets of a corporation, the earnings record, the dividends paid, the future prospects of the company and the qualitative factors of management. Intrinsic value is not a firm price, but an estimation of a fair value. It is used as a guide to determine if the current market price is low enough in relation to this value to justify a purchase with a reasonable margin of safety. Or that the price is so high that it is justified to take profits or refrain from purchasing. An Example: Emerson Electric Company (EMR) As Benjamin Graham was quite famous for his use of real time examples, we thought we would share with you an example from our own holdings in Emerson Electric. Emerson was founded in 1890 in St. Louis, Missouri as the manufacturer of electric motors and fans. In the past 100 years, they have grown into a diversified manufacturing company that operates 235 manufacturing facilities throughout the world. With a global workforce of approximately 133,000 employees, they hold an industry leading position, making the company a single source for any customer in any country to help them meet their infrastructure solutions, including process automation, plant optimization, telecommunications, reliable network power, climate control and more. Since October 2000, David N. Farr has led the company as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. The Board of Directors consists of individuals from around the world including Harriet Green from London the CEO of Thomas Cook Group, plc, Carlos Fernandez from Mexico, the Chairman and CEO of Grupo Modelo SAB. Clemens A.H. Boersig the retired Chairman of Deutsche Bank AG. They also include St. Louis’ August A Busch, III, Retired Chairman of the Board, Anheuser-Busch Companies, Inc., along with Randall L. Stephenson, CEO and President of AT&T, plus others of equal standing within the world community. As David Farr is one of a few individuals who have led a major corporation as CEO for over a decade it serves us well to look at his and the company's record of performance. We will limit our information to the last ten years. Source: Value Line It doesn’t take a security analyst to briefly review these numbers and draw a conclusion that this company has not only been well managed, but they have also been shareholder friendly. The company’s results over the past ten years are enough to have passed my qualitative test of managements’ capabilities. In addition to the operating results listed above, the company has never overextended its leverage with debt representing 34% of total capital. Value Line gives the company its highest rating for financial strength A++. S&P gives them a credit rating of A and due to their consistent operating results and decades of annual dividend increases an A+ Quality Rating for the company’s shares. Although we have given a passing grade to the qualitative factors of Emerson, it doesn’t give us the voting record. The price earnings multiple is a readily available measurement that helps us judge how the investing public has used their own analysis and emotions to place a market price on the shares of Emerson. The following table lists both the high and low multiple of past earnings for ten years. As you can see, the public has recognized the qualitative factors reviewed above with an earnings multiple that, on average, is high. Emerson recently reported the final quarter earnings for fiscal year 2012. For the trailing twelve months, the company has earned $3.39 per share. In addition to our record listed above, the company has raised its dividend twice and currently is scheduled to pay $1.64 per share for fiscal year 2013. Using the average ten year multiples listed above and the company’s most recent earnings we would have a range of $50.90 ($3.39 x 15.02) to $74.27 ($3.39 x 21.91). At the current price of $48.19, and with expected earnings for fiscal year 2013 of $3.60 per share, we believe that Emerson can be purchased at the present quotation. We can also conclude that the intrinsic value of Emerson shares are well above this quotation providing the long term investor with an adequate margin of safety.

As value investors know, price is the most important factor in investment decisions. Without some method to determine a fair price you cannot, nor will you ever, be an investor, you will be a speculator, with your returns almost exclusively the result of luck. If you consider yourself lucky, then by all means take a chance. The rest of you will be far better off relying on the use of intrinsic value and a margin of safety in the management of your portfolio. Until next time, Kendall J. Anderson, CFA Comments are closed.

|

Kendall J. Anderson, CFA, Founder

Justin T. Anderson, President

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Common Sense Investment Management for Intelligent Investors

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed