|

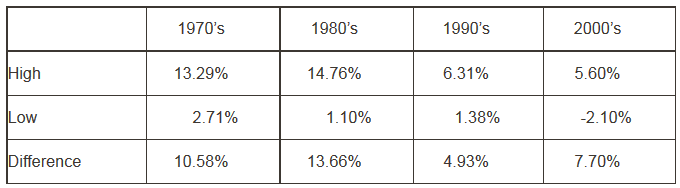

Counter-steering For years, our tag line “Common Sense Portfolio Management for Intelligent Investors” has served us well. There are times, though, that “Common Sense” can steer us in the wrong direction. Take driving. When a teenager sits behind the wheel of a car for their very first attempt at driving they know, from years of watching Mom and Dad drive, that when they want the car to go to the right, they turn the steering wheel to the right. Even someone who has never driven an automobile knows this. It is common sense. What if, to turn right, you actually had to turn the wheel to the left? That just doesn’t seem right. Why in the world would anyone do such a silly thing? Yet on a motorcycle, that is exactly what you need to do once you exceed a few miles per hour. To turn right, you first lean the bike to the right and slightly push the front wheel to the left. The faster you are moving, the more force you need to use to lean the bike and negotiate a turn successfully. This “counter-steering” becomes natural for new riders with very little effort. If it doesn’t, the rider will most likely feel the pain of sliding across the pavement or the thrill of flying off the bike as it and the rider run straight off the road. I’m afraid that a large number of people may be feeling the pain of counter-steering in the bond market sometime in the near future. A recent survey of self-directed 401K investors asked a simple question: If interest rates go higher, will bond prices go higher? For a long term owner of bonds or bond mutual funds, this is simple to answer. For first time investors, common sense may get in the way. In the late 60’s Sidney Homer was a well known and respected individual who wrote about interest rates and the bond markets. In an engaging book titled The Bond Buyer’s Primer,he told a story about a conversation a bond trader named George had with his wife after a tough day at work. Wife: How was the bond market today, George? George: Down again. Wife: Goodness, again? Hasn’t it been going down for a long time? I hope that isn’t bad for you. George: Bad and good. Of course, prices are down and we have some losses but the interest rates on bonds are getting better and better – they are really going through the roof – haven’t been so high in thirty years. Pause Wife: Now, George, I just don’t understand and I wish you would explain. You say that bond prices are going down and at the same time that the interest rates bonds pay are going up. That doesn’t make sense. If they pay more interest certainly they would go up in price; at least that couldn’t possibly put them down. Don’t people want more interest? Of course, they do. I am sure I keep misunderstanding you. It has become natural for us in the investment business to know that when interest rates go up, bond prices decline. Yet, more than 50% of self directed investors in 401k’s seem to have the same common sense as George’s wife and believe that higher interest rates will increase the price of their bonds. Since so many believe this we want to take a little time this month to create a very short bond market primer. A Few Basics The price of a bond, or for that matter, any loan that carries a fixed interest rate is the total of all the cash the investment will pay in both interest payments and principal payments discounted by the current rate of return available to a new investment made today. Because interest rates can change at any time, a current bond’s market price will change as the current rate of interest changes. It might be easier for you to think of this; let’s say you invested $100,000 in a U.S. Treasury Bond that paid you $1500 (1.5%) per year and repaid your principal in 10 years. After a year, you needed the money for some other purpose so you decided to sell your bond. Over the year interest rates went up by 1%, so that someone with $100,000 could invest in a U.S. Treasury Bond that paid them $2500 (2.5%) per year and repaid their principal in nine years. Do you think they would buy your bond from you for $100,000 when they could earn a whole lot more than your bond will pay them? Of course not! They would only consider buying your bond if the total interest paid to them at least equaled what they could earn by buying the new bond. In order for your bond to yield the new investor 2.5% you would have to sell your bond to them for $92,000 plus or minus a few bucks for commissions. A loss of about $8,000 in a year that you thought was risk free when you bought the bond. Of course if interest rates went down 1% so that someone with $100,000 could only earn $500.00 (1/2%) per year for next nine years they would love to own your bond. Would you be willing to give up an extra $1000 per year and let them have your bond for $100,000? Of course not! As an intelligent investor you would want more for your bond. If you sold the bond so that it equals what they would receive on a new investment you would ask them to pay you $108,800 plus or minus a few bucks for commissions—a gain of over $8,000 in a one year. Not bad! To sum up, changes in the market value of a bond are inversely related to changes in the yield to maturity. The longer the bond guarantees the same fixed interest payment, the greater is the chance that you will make money or lose money. That is easy enough to understand. Interest rates change very little in a few months or a year. And even if they did, you could just hold on to your bond and let it mature. The longer it is until the principal is repaid, the greater chance that interest rates will rise or fall affecting the market value of your bond. If it was a very long time, say 10 – 20 – 30 years interest rates could change for all kinds of reasons leaving you with a big loss or gain if you needed to raise cash quickly. Most of you would feel pretty good if it was a gain. But could you also feel just as good if it were a loss—especially if you invested in the bond to preserve principal and pay income. The lower the fixed interest payment on your bond, the greater is the risk to your principal if interest rates rise. Remember that a bond’s market value is the total of all the cash the investment will pay in both interest payments and principal payments. In our example above, if we changed the beginning interest rate to 8% a 1% increase would reduce the market value of your bond to 94,000. A decrease of 1% to 7% would increase the market value of your bond to 106,500, plus or minus a little bit for commissions. The higher the possibility that the borrower will not be able to pay your interest and principal at maturity, the more current interest you will receive, but at a price of not getting your money back. This risk of loss will be reflected in the market price. A negative change in the borrowers’ credit quality could take over the valuation no matter what happens to interest rates. Now we know that current interest rates, years to maturity and the credit quality of a borrower all can impact the market price of a single bond. But what if you owned 100 or 200 bonds all with different interest rates, different maturities and different credit qualities;would it be possible to estimate what would happen to the value of the entire pool of bonds if interest rates change? Luckily, the bond mathematicians got to work and developed a way for all of us to answer this question. They call it duration. I have no desire to get into the math of the various forms of duration (Macaulay, Modified or Effective), nor do you unless you just have a great desire to do a little math for fun. The reason you will not need to do the math is simple. If you own 100 to 200 bonds you would be a pretty big investor and your advisor will do the work for you. If you own shares in a bond mutual fund, the bond manager will report the duration of the portfolio to most of the mutual fund rating agencies. Of the three forms of duration, modified and it’s more complicated cousin, effective duration, are the ones you should pay attention to. They both measure the change in the market value of the bond portfolio for a 1% change in interest rates. Here is what you need to know: As the average maturity of the bonds held in the portfolio increases, the duration of the portfolio increase. With a longer duration, the total market value of the portfolio will increase and decrease more with a change in interest rates. As the current interest paid on the portfolio increases, the duration of the portfolio decreases and the change in market value will increase and decrease less with a change in interest rates. If the overall level of interest rates increases, the duration of the portfolio will decrease and the market value will change less with a change in interest rates. Morningstar reports effective duration of the fixed income mutual funds submitted for their database and review. As of September 30th, there were 356 intermediate government bond funds in their Principia database that had reported their results. The average effective duration of these funds was reported as 3.6. What that tells you, is that if interest rates increase by 1% the average market value of all these funds together would decline by 3.6%. If interest rates increase by 2% the average market value all these funds together would decline by 7.2%. For every additional 1% increase the total value would decline by an additional 3.6%. Inflation Understanding how the market values your bonds is important. However, what is more important is what the primary driver of interest rates over time will be. In my book, that driver is inflation. We all know that inflation robs us of buying power. Think of it this way. If four years ago you purchased a bond that paid you $100 interest per year you could take that $100 and buy about 55 gallons of regular gas. Today that $100 would only buy you about 25 gallons. Your fixed income investment did what it was suppose to do – pay you the same amount of money yearly, yet it did not do what all investors should strive for, to preserve their purchasing power. Because inflation silently takes away our purchasing power and we know it, interest rates, in normal times, will equal the inflation rate plus a premium to that rate to protect your purchasing power. Recently that normal premium has been lacking in the fixed income market. My thoughts are that the pure fear of losing money in the stock market, the positive rates of return on bonds over the past few years and the very low level of core inflation has taken our eyes off the need to preserve purchasing power. Because inflation silently does its dirty deeds, we sometimes fail to remember the inflation rate is nowhere near stable over time. In fact, the rate of inflation has been and will continue to be in the future highly volatile. I thought it would be helpful for you to see the changes in the rate of inflation over the past four decades. Here they are: Inflation by decade Source: JP Morgan

Over the past seven decades the inflation rate in the United States has averaged about 4%. In the past decades it has only averaged 1.75%. As we know, the last decade and a half was an extreme period of time in our history with both stock prices and home prices blowing up, causing severe losses in our net worth and threw our economy into a couple of recessions. As the economy heals and the impacts of those two disasters fade from memory, inflation will begin its ascent and bond prices will reflect this. Intelligent investors need to recognize when their “common sense” is sending the wrong signals. Knowledge of how things work under different situations is your best defense. We are always available to share our thoughts with you. Just give us a call. Until next time, Kendall J. Anderson, CFA Comments are closed.

|

Kendall J. Anderson, CFA, Founder

Justin T. Anderson, President

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Common Sense Investment Management for Intelligent Investors

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed