|

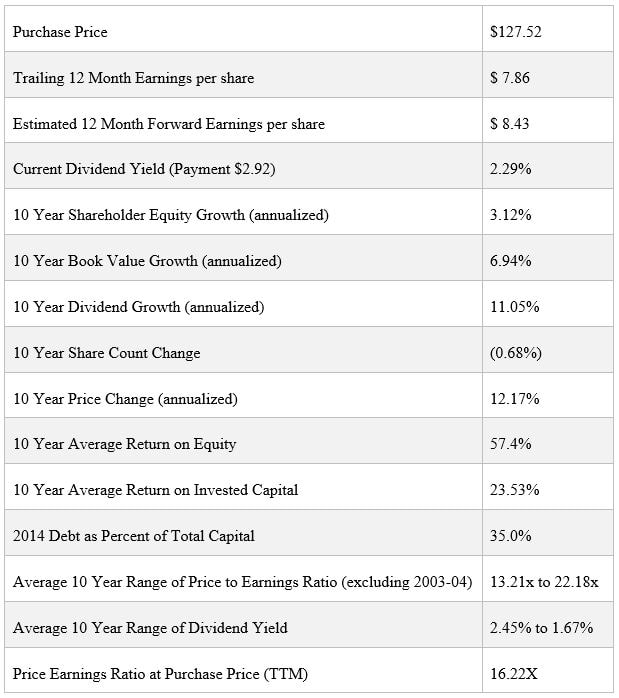

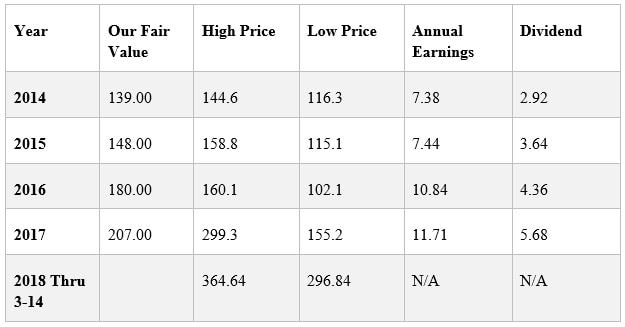

From the time I was a little tyke, I knew the benefits of having cash available to make a purchase. With it I could easily buy something under very favorable terms when others were in desperate need of that cash. Maybe that drive to make a purchase at a bargain price is in my DNA, or it might just be from following my Mom around to all the yard sales in town, watching as she bargained to save a nickel. So it should be no surprise that when I discovered the value approach to investing it felt right in every way. Buying a small ownership in a business, via the public securities market, at a price that was less than the value I could reasonably place on the entire business just made sense to me. Shortly after I began this journey into professional portfolio management as a value investor, I found that it doesn’t take very well with the majority of individual investors. And it has almost zero appeal to the mass army of financial advisors working on behalf of broker-dealers or investment consultants guiding their institutional clients. Value investing does not appeal to the get rich quick crowd, nor does it fit into a predetermined bucket based on one or two single factors like price-to-book or price-to-earnings. Not to mention that the academics who study markets state that any outperformance that comes with value investing is simply the reflection of a higher level of risk. Value investing is not contained to any single type of investment or market. It is universal in its application to common stocks, bonds, real estate, or any other type of asset that has potential to generate future cash flow. The problem, as with all investing, is that the amount of future cash flow is never certain. For common stocks, both the amount of cash flow and the timing of when that cash flow (if ever) will be paid are uncertain. Because of this risk inherent in all types of investing, each of us will have to apply some form of risk reduction to reduce the impact of uncertainty. The primary method of reducing risk is through diversification and asset allocation. In addition to these broad categories, value managers believe that purchases of common stocks require a margin of safety. This means buying when the current market price is less than the fair or intrinsic value of the entire enterprise as calculated using publicly available information. What is interesting is that most individuals and professional investors think that common stocks have less risk when prices are high relative to fair value. It is why the buy high, sell low club continues to add members. I believe that most professional advisors buy into the academic studies on market efficiency. By doing so, they universally believe that the larger the company, the more accurate its current market price. In fact, they believe that the price is so accurate in reflecting all current and future information that any attempt to profit from fundamental analysis is useless. Of course this is the exact opposite of what we believe and have practiced with very good results over multiple decades. We have found that more believers in the efficiency of markets increases the opportunities for fundamental value investors to profit over time. Buying large companies at cheap prices happens during times of market distress, or as our subject company this month shows, when a problem arises that will have limited impact on the company’s longer term performance. News, real or fake, the psychology of fear and greed, and momentum drive short-term prices up and down. Those who believe that the market price is always right help create the opportunities to buy with a margin of safety or sell when that safety is absent. Discipline One of the best introductions to value investing is Seth Klarman’s The Timeless Wisdom of Graham and Dodd. It is the preface to the sixth edition of Benjamin Graham & David Dodd’s Security Analysis. We borrowed Patience, Discipline and Risk Reduction from this work for this month’s letter. We thought we would do as Benjamin Graham did so often in his writings, and explain these characteristics by reviewing an investment, in this case our investment in Boeing Company, from our purchase, through our holding period, and to our ultimate sale last month. Boeing Company began over one hundred years ago and today is the world’s leading manufacturer of commercial aircraft. In addition, the company manufacturers military aircraft, rotorcraft, electronic and defense systems, missiles, satellites, launch vehicles, and advanced information and communication systems. It is one of the largest exporters of manufactured goods in the United States, and is one of 30 companies included in calculating the Dow Jones Industrial Averages. Data for the Boeing Company (BA) when purchased September 14, 2014 After a brief look at the table above, one could easily draw the conclusion that this company should never be considered as a value investment. And of course, according to the academics, you would be right in concluding that Boeing is not a value company but a growth company. Yet our approach is not based on academic or index providers’ calculations. As Benjamin Graham stated, “The price [of a security] is frequently an essential element, so that one stock may have investment merit at one price level but not another.” The reference to price is the root of the value philosophy. That is, market participants set the daily price of all publicly traded securities. As such, they create opportunities to buy an ownership interest in a company at a bargain price. At other times, they create the opportunity to sell an ownership at a price at or above a fair value. Prior to every purchase we ask ourselves “Why is this company cheap?” In Boeing’s case, two items stood out. Perhaps you remember that in 2013 the market return was exceptional. The S&P 500 advanced over 30% and the Dow Jones by over 26%. The shares of Boeing were the best performing stock in the Dow Jones Industrials that year. After Boeing reached an all-time high in January of 2014, its share price quickly reversed. Most analysts blamed this on a proposed reduction in defense spending. We simply thought it was an excuse for people to take profits. In addition, in the year following such a large return in the markets, a vocal minority of investors led many to believe that a crash would come soon. Selling continued throughout the year, with the price of Boeing shares registering the worst performance of all the Dow components. Yet, the company raised its dividend by 50%, increased their backlog to over $400 billion, and reported the most profitable quarter in their history. However, concerns continued to swirl around defense cuts and the development cost of the company’s wide-body jet projects, the 787 and 777, both of which seemed to be of little importance for an investor with a long-term outlook. At the time of purchase we placed a fair value on Boeing shares of $139.00. That is approximately the mid-point of our calculated range of valuations which are based on actual earnings results, not forward estimates. It requires discipline to buy based on actual results in lieu of forward expectations. It is much easier to buy based on the stories of what may happen. Yet we have learned through experience that the future may look clear today, but seldom happens as expected. Patience Data for the Boeing Company (BA) from September 14, 2014 - March 14, 2018 Mason Hawkins, the well-known manager of the Longleaf Partners Fund, used the terms “Time Arbitrage” to describe his investment philosophy. This concept is well known among value managers. Buying a good business at a price that is cheap, but with good potential for future growth, can produce long-term superior returns. It just takes the patience to hang on until others recognize the value and bid up the price. As you can see, we had a long wait. Two years after purchase we were still a bit underwater on our price paid. Yet the business was continuing to perform well. Earnings, dividends, order backlog, and current deliveries were increasing year by year, and therefore increasing the value of the business. Ultimately, the market came to the same conclusion we did, and bid the price up to beyond our range of valuation, at which time we sold our shares. Risk Aversion Risk aversion ranges from those who will never take any risk of loss and hold only cash, to those who embrace the maximum level of risk and are willing to bet it all. A value investor understands it is necessary to accept the risk of being wrong, but insists on some margin of safety when investing in any common stock. In our approach we will only invest at a price less than our calculated fair value, the larger the discount the better. As we all know, valuation is an art, not a science, thus the need for a range of valuations. We also must recognize that valuations change over time as a result of unknown events, so constant attention must be given to new events, and adjustments made to any valuation range to reflect those changes. We will sell if the current price exceeds the upper levels of our calculated value. I will end with a few words from Seth Klarman’s preface: In a rising market, everyone makes money and a value philosophy is unnecessary. But because there is no certain way to predict what the market will do, one must follow a value philosophy at all times. By controlling risk and limiting loss through extensive fundamental analysis, strict discipline, and endless patience, value investors can expect good results with limited downside. You may not get rich quick, but you will keep what you have, and if the future of value investing resembles its past, you are likely to get rich slowly. As investment strategies go, this is the most that any reasonable investor can hope for. Until next time, Kendall Comments are closed.

|

Kendall J. Anderson, CFA, Founder

Justin T. Anderson, President

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Common Sense Investment Management for Intelligent Investors

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed