|

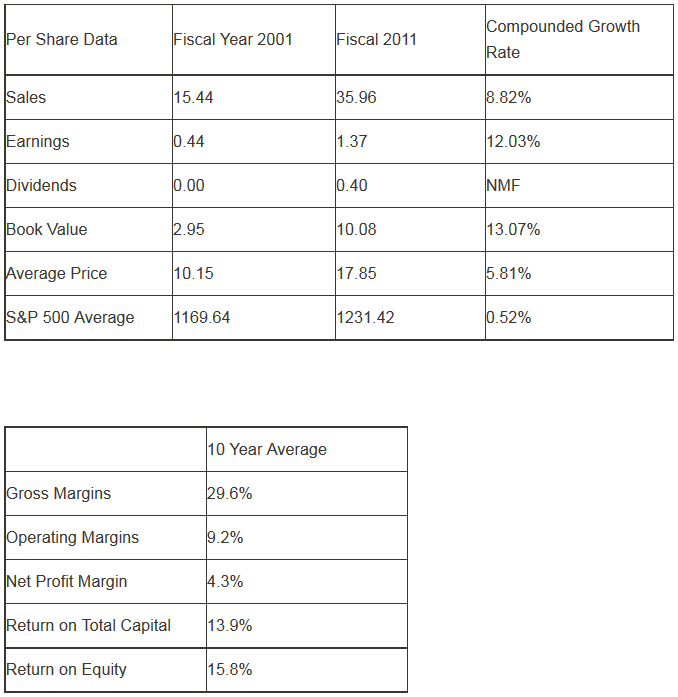

On February 25, 2012, Warren Buffett released his letter to Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders. Towards the end of his discussion on the rationale for the purchase of IBM (shares of which I have personally owned for the last five years) was this paragraph: Charlie and I don’t expect to win many of you over to our way of thinking – we’ve observed enough human behavior to know the futility of that – but we do want you to be aware of our personal calculus. And here a confession is in order: In my early days I, too, rejoiced when the market rose. Then I read Chapter Eight of Ben Graham’s The Intelligent Investor, the chapter dealing with how investors should view fluctuations in stock prices. Immediately the scales fell from my eyes, and low prices became my friend. Picking up that book was one of the luckiest moments in my life. I think most of us can agree that Mr. Buffett has created his own luck over the years. Some may consider obtaining a job with Benjamin Graham was his luckiest day. But for those of you who blame others’ success on luck should remember that his job only came about after he offered his services for free! My Lucky Day My introduction to Ben Graham’s Intelligent Investor truly was lucky. When I graduated from college, the only job offers that came my way paid me substantially less than I was making as a student. I remember one company that told me they were offering me more money than they have ever offered a new graduate. It was a respectable offer, but with a wife, two kids, and one more on the way, their offer still would have required me to make a choice between working for them or letting my kids go hungry one or two days a week. My choice was simple – the kids had to eat! So off I went to the nearest city, Little Rock, Arkansas to attend graduate school and find a job. I know that those of you who live in a metropolis might think Little Rock is not a city, just a little town in the middle of nowhere. But for someone who grew up in Iowa, who went to a little college in a little town in Arkansas, Little Rock was a city to me. And Little Rock had lots of jobs that paid pretty well. For whatever reason, some might call it luck; I took a job with Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner and Smith. Not because they offered me a giant salary, but because their office was just a couple of blocks from the University where I was attending classes. Besides, my family could surely live for a couple more years on a diet of spaghetti, macaroni and cheese and hamburger. Looking back, my time at Merrill was lucky. It introduced me to people who made their own way in life through hard work. These people showed me that if you have a dream, it is possible to make it come true. Of course Merrill also introduced me to the investment profession. To me, being an investment professional had great appeal, but the city… well the city just had to go! So with family in tow, we headed back to Iowa where I ran into an investment firm looking to hire a salesman. The firm was Edward D. Jones & Company who today, under the shortened name of Edward Jones is one the nation’s largest. When I took a job with the company it had about 200 offices staffed by one salesman throughout the Midwest, including a couple in Arkansas. I added to that number by opening up shop in Paragould, just a few miles from the boot heel of Missouri. Paragould was about twenty miles from Kennett Missouri, the home town of an Edward Jones Partner, Ron Lemmons. Ron had operated a successful office for Edward Jones in Nebraska during the sixties and seventies. And of course, living in Nebraska and knowing the investment prowess of Warren first hand, Ron never hesitated when I asked him for guidance. He told me that I should read Benjamin Graham’s Intelligent Investor, the only book I’ll ever need. It was my lucky day! Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor I cannot think of a better way to introduce this book to you than to reprint a portion of Warren Buffett’s Preface to the Fourth Revised Edition. I read the first edition of this book early in 1950, when I was nineteen. I thought then that it was by far the best book about investing ever written. I still think it is. To invest successfully over a lifetime does not require a stratospheric IQ, unusual business insights, or inside information. What’s needed is a sound intellectual framework for making decisions and the ability to keep emotions from corroding that framework. This book precisely and clearly prescribes the proper framework. You must supply the emotional discipline. If you follow the behavioral and business principles that Graham advocates—and if you pay special attention to the invaluable advice in Chapters 8 and 20—you will not get a poor result from your investments. (That represents more of an accomplishment than you might think.) Whether you achieve outstanding results will depend on the effort and intellect you apply to your investments, as well as on the amplitudes of stock-market folly that prevail during your investing career. The sillier the market’s behavior, the greater the opportunity for the business-like investor. Follow Graham and you will profit from folly rather than participate in it. Unlike Mr. Buffett, the first time I read Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor scales never fell from my eyes, but it did help me recognize the selling pressure a brokerage firm can place on their brokers. It took seven years and a market crash to clear my vision and even then, another decade to fully recognize what Warren Buffett recognized at the tender age of nineteen. Since then the fifth and last version of the book has been within reach of my desk. As far as I am concerned, Chapter Eight’s twenty-one pages titled “The Investor and Market Fluctuations” should be required reading for every individual investor. This chapter covers trading, market timing, formula plans, private equity, bond prices, and is also our first introduction to Mr. Market and his bipolar personality. Chapter Eight on Bonds There are only five pages dedicated to bonds in Chapter Eight. But, these five pages had such major influence on my early years as an advisor. And once again, it is those pages that are sending me a reminder as to why I should not buy bonds today. Given the current interest rates, I would strongly suggest any and all bond investors read these pages. I can assure you that Mr. Buffett has. It may be one of the reasons he made this statement in his Chairman’s’ Letter: Beyond the requirements that liquidity and regulators impose on us, we will purchase currency-related securities only if they offer the possibility of unusual gain – either because a particular credit is mispriced, as can occur in periodic junk-bond debacles, or because rates rise to a level that offers the possibility of realizing substantial capital gains on high-grade bonds when rates fall. Through we’ve exploited both opportunities in the past – and may do so again – we are now 180 degrees removed from such prospects. Today, a wry comment that Wall Streeter Shelby Cullom Davis made long ago seems apt: “Bonds promoted as offering risk-free returns are now priced to deliver return-free risk.” In the investment business, you learn quickly that customers find it very easy to buy what did well over the past ten years and reject anything that has done poorly. Of course, this is a problem for a believer in value investing. Ron Lemmons’ recommendation to me took place in 1980. In 1980 common stocks had not made a dime for the average investor for more than a decade. Bonds were nearing the end of a forty year bear market. Think of that, bonds had not preserved wealth for forty years! So what was a financial salesman to do? The easiest solution was to sell whatever the customer was willing to buy. And in the early 80’s that product was real estate. Wall Street had found a way to package real estate and sell it to individual investors. These products were structured as Limited Partnerships. The General Partners loved these products, the brokerage firms loved to sponsor them, the salesman earned on average an 8% commission, and, best of all, the people would buy them. This was because real-estate had just gone through an inflation driven, ten year appreciation period that made the real-estate bubble look mild. But, I couldn’t sell them. Unlike many of my peers, I actually took the time to read the partnership documents, understand the structure, and asked myself a simple question: How could these things make any money for the limited partners? A few actually had some good qualities, but the majorities were designed in such a way that the actual investor never had a chance. (Time proved this was the case, as the majority of these partnerships filed bankruptcy). Needless to say, I was close to failure as an investment professional. Commissions, absent the easy sale, were slim. My kids were still hungry and the outlook was dim. And that is where Ben Graham’s five pages on the history of bond prices saved the day. This is the single sentence that changed everything for me: In mid-1970 the yields on high-grade long-term bonds were higher than at any time in the nearly 200 years of this country’s economic history. And in late 1980 bonds yield were even higher than in 1970!! Over the next seven years I sold as many bonds as I could to anyone who would listen. GNMA’s with a coupon of 8% could be bought at between 50 to 70 cents on the dollar. AAA rated municipal bonds earning 12 to 14% yields to maturity. Long-term FDIC Insured CD’s paying 10% to 15% and higher. And my favorite for college savings were long-term U.S. Government zero coupon bonds with yields to maturity exceeding 10%. Think about those yields when you look at rates paid today. 1 Mo 3 Mo 6Mo 1 Yr 2 Yr 3 Yr 5 Yr 7Yr 10 Yr 20 Yr 30 Yr 0.08% 0.09% 0.15% 0.19% 0.28% 0.42% 0.85% 1.37% 2.01% 2.77% 3.13% U.S. Department of the Treasury resource center daily rates for April 11, 2012 For those of you thinking of investing in bonds, think again. Today, unlike 1980 when the yields were at their all time highs, average yields on bonds are challenging to become the lowest rates ever in the 236 years since our country’s Independence. Chapter Eight on Stocks – The Staples Example Benjamin Graham, the teacher, always recognized the use of examples to clarify an idea. The examples used in the The Intelligent Investor are, as you would imagine, quite old. For many readers, a discussion on Northern Pacific 3s due 2047 or The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe general mortgage 4s due 1995 places the book into the history category. The same holds true with his use of the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. stock to discuss share price fluctuations based on a price history from 1929 to 1972. I believe this is the reason so few people will read the book once, let along multiple times. So I thought I would update an example for you. The Staples Example I have chosen to use as an example Stapes, Inc. (SPLS). Besides being an owner of Staples Common Shares, Staples has a particular connection to the grocery store business, (Graham’s example – A&P) and for those who care about the upcoming Presidential election, the leading Republican Candidate for the Presidency, Mitt Romney. Here is the story: Tom Stemberg learned the retail business from his time at Star Market a New England chain of supermarkets. His idea was that small business owners would drive to a mega-store to buy their office supplies. This is something many of us take for granted today, but, at the time, this concept was considered ridiculous. But Mr. Stemberg had learned from his years in the grocery business that you can make a lot of money with a small mark-up as long as you sold in volume. He also knew that people would drive to a mega-center to buy their office supplies just like people drive to a grocery store if the savings were substantial. He enlisted the help of Leo Kahn who turned a wholesale business into the Purity Supreme grocery chain which was sold to Stop & Shop. In his late sixties at the time, Leo Kahn was an experienced entrepreneur with a great reputation. He knew that the neighborhood stationery stores controlled the market for office supplies— and that created a very costly distribution system. All Tom Stemberg and Leo Kahn needed was the capital to open their first store. Most sources of capital laughed at the idea of an office supply mega store. This included most of the partners at Bain Capital, an upstart venture capital firm led at the time by Mitt Romney. But Tom and Leo pushed two points; Small business owners never realized how much they spend on office supplies and the growing number of self-employed individuals who work at home would be a stable customer base for discounted stationery. Bain went to work to validate Tom & Leo’s claim. From their research they learned that small business owners were spending far more on office supplies than they realized. They also learned that small business owners would drive to the store if they could save at least half of their current spend. With Mitt Romney leading the debate to invest the partners’ money, Thomas G. Stemberg and Leo Kahn received a $1 Million capital infusion to open the first office products superstore in Brighton Massachusetts. The year was 1986. In 1988 Staples brought in Henry Nasella the former President of Star Markets to oversee the company’s rapid growth. Staples IPO took place on April 27, 1989 issuing 3,250,000 shares at $19.00. Since then it has split eight times. The adjusted cost per share for the original owners who retained their shares is $0.74. From a single store in 1986 the company has grown its operations rapidly with operations in North America, Europe, Asia and South America through 1,917 stores today. In addition, the company sells Staples branded products in over 2400 grocery stores. Staples is considered the leading office products company in the world. Over the past ten years the company’s results have been impressive. In 2001, the range of Staples share price was $7.30 to $13.00. In August of 2011 Wall Street determined that the total value of Staples was worth only $11.94 per share. This is less than Wall Street valued the company for the majority of the year 2001 and every year thereafter. Why? According to Wall Street it is because International operations are under extreme pressure and small business profits are weak causing North American retail operations to suffer. The end result will be a continuous decline in earnings.

Both of these reasons seem temporary to me. In addition, these temporary reasons mask what a proven management team is doing. Today the company’s delivery operations represent more than half of their business. Their internet retail business is second largest in the U.S. with only Amazon being larger. And their well respected and long standing sales force can be leveraged to help managements meet its goals of expanding into facilities management. Let’s assume you buy the shares today at $16.00 per share. This is just 11.7 times trailing earnings. In the last ten years shares of Staples have only traded at this low of a multiple twice— in 2008, during the peak of the financial crisis, and last year. The average multiple given to Staples for the last decade is 16.9 times trailing earnings, which equates to a price of $23.15 or 45% above the current quote. Some final notes Ben Graham’s legacy to common stock investors can be summed up with these three maxims:

Kendall J. Anderson, CFA Comments are closed.

|

Kendall J. Anderson, CFA, Founder

Justin T. Anderson, President

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

|

Common Sense Investment Management for Intelligent Investors

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed